Christoph Niemann für Freunde von Freunden

Vor Kurzem haben wir Christoph Niemanns Vortrag auf der TYPO Berlin gesehen, der die große Hall mit seinen eindrucksvollen und so witzigen Arbeiten zum Lachen gebracht hat. Dabei ist er als Mensch ganz bodenständig geblieben.

Freunde von Freunden haben ihn in seinem Atelier besucht und ein schönes Interview mit ihm geführt, das wir euch an dieser Stelle ebenfalls präsentieren möchten.

Text: Liv Siddall

Photography: Robbie Lawrence

If you ever wander down Schröderstrasse in Mitte, keep your eyes peeled for a little ground floor window with a small frame within it. Every now and again, cartoonist Christoph Niemann places a small item of curiosity in this frame that he exhibits for the public’s viewing pleasure. Inside the building is his studio, from which he grins at passers by as they stop and blink at the window, examining the artefact he’s chosen to display.

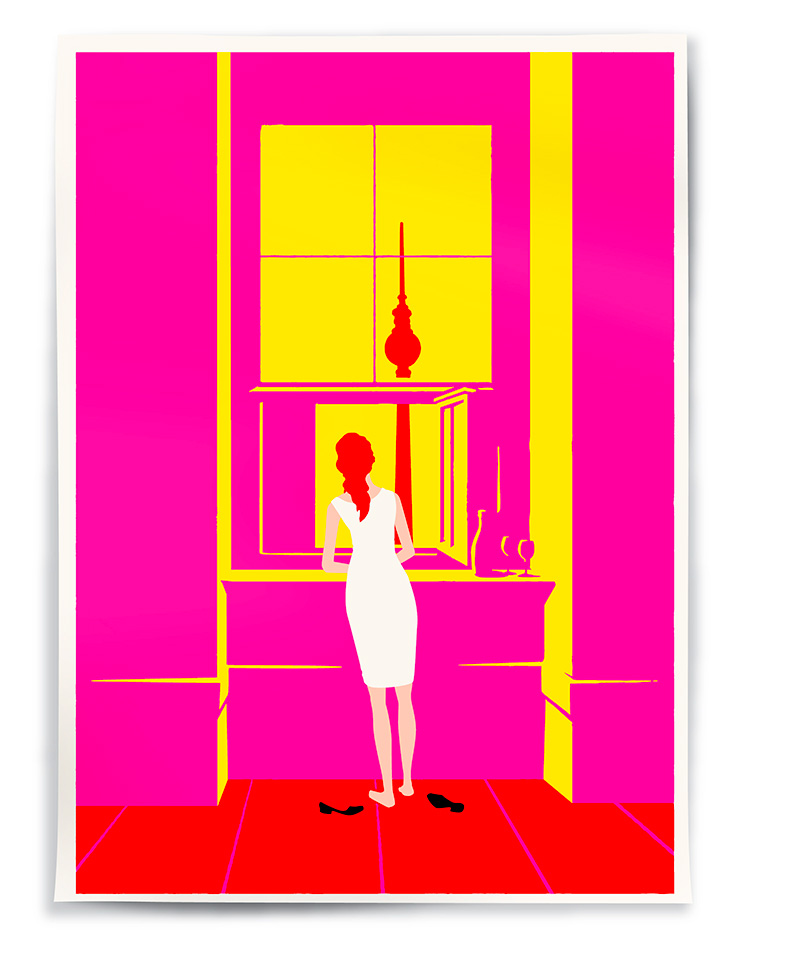

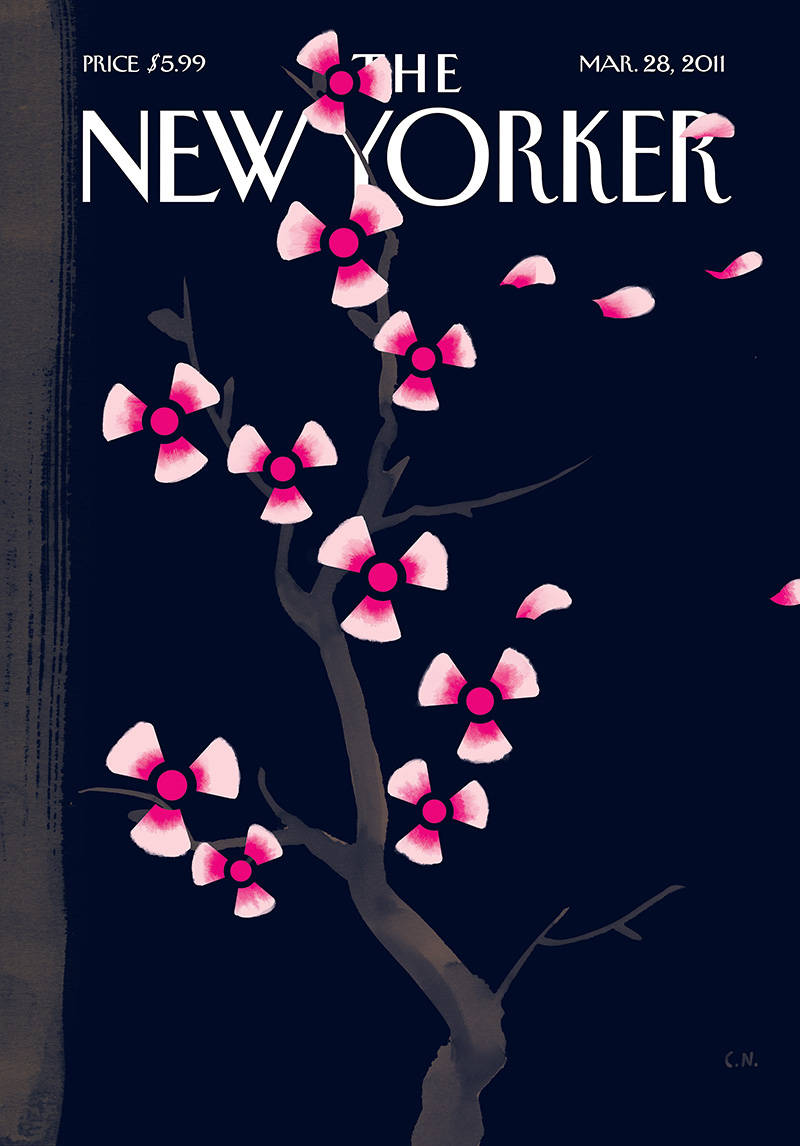

With high-end commissions predominantly from across the Atlantic – including editorial work for The New York Times Magazine and covers for The New Yorker – Christoph may appear to be masquerading as an American. In fact, he was born in Stuttgart, spending 11 years in New York before moving to Berlin with his family. This is where he works today, churning out cartoons, magazine covers and witty illustrations in his shiny, cosy studio which backs right on to his house.

Pots of ink, jars of pencils and brushes, an ever-changing gallery wall and an enormous archive of prints surround Christoph as he works: everything is neat as a pin and in its correct place. As a quick-witted cartoonist, he’s something of a rare beast in this day and age. But that’s what’s so magical about him: he’s a master of his craft, creating ink drawings with a flick of the hand and a deft movement of his brush. And even though he’s slightly bewildered at the sudden introduction of social media to the world of illustration, he’s riding the wave happily.

Here’s Christoph on the importance of a functional studio, the perils of pulling an all-nighter and the importance of being as inefficient as possible.

At first you were worried that an interview would disrupt you too much to work. Do you structure your days very strictly?

I’ve got the whole thing so tightly organised. The kids go to school and are out at eight, and then the clock starts running. They come home at four or five and they do their own thing, but at six, it’s over – so I have to get everything done in that time. Over the years I realised: I always knew that you can only get so much creative work done in a day, but now I feel like I’ve perfected this system so much that it’s dangerous if I mess with it. I mean, an all-nighter? Stupid. Working in the evenings? I suppose sometimes you have to. But you pay the price the next day. I found keeping a rhythm of five days a week with perhaps some emailing on top is really the most I can do. And If you mess with the system, it’s really bad. I try not to do lunches with clients anymore. You can’t get that time back. It’s never just one hour taken out of the day, and the whole system falls apart.

When do you tend to work best?

Definitely the morning. There’s something about the freshness of 8:30. I don’t know if it’s age or having a system, but I run out of steam. I realise when I do six or eight hours, there’s nothing left. That’s when you start ruining drawings and making bad decisions.

When you were looking for a house, were you looking for one that had a built in studio?

No, not at all. I’ve had about five different studios in Berlin since living here. Once I had a studio that was a lot of fun in the official press building of the federal government, right on the river. I could see trains and ships and it was across the river from the Chancery. After that, there was a building full of artists and architects just a few blocks from here, and I moved three or four times within that building. The main problem was not having enough space – I don’t know if it’s changed with me or the world at large, but I felt when I started out that it was all about the work. Your career is something that happens in the printed piece, and you, your opinion, your environment and your sketches play no role. Nowadays there’s social media, and I feel it’s almost impossible to leave yourself out of it.

With most assignments I get now – not all – people want a video, too, so you spend two days doing the drawing and then spend four days doing a how-to interview to accompany it. And of course, it has to be in your studio, so I realised there was value in having a good place to show where your work happens. It used to be that my studio was a total mess, and it didn’t matter because I could work there. Eventually, I realised that curators and collectors come to look at drawings and you need to be able to make a statement with your environment. It’s something I didn’t want, but I realised I had to make up for the lack of that with even more work, and even more drawings. I realised when I had this place that it’s actually fun to have a space where you can hang things on the wall, and where I can have a big table where I can sit down and draw. It’s so much easier. You don’t have to compensate so much.

Tell me about the wall in your studio that serves as a mini exhibition of your work.

When I moved in, I worked with this really young architect, a fantastic guy called Martin Hösl. We talked about what we wanted to do with the wall and I said, “When things come from one show to another show, I want to be able to store them on the wall.” It also allows me to look at my work, so when there’s a new show, I can say, “Okay, why don’t we use this and this?” It gives me a chance to look at the pictures and see how they work together. When they are in boxes, you just forget what’s there.

Many of your projects, such as your work for The New Yorker, are commissioned regularly. How much do you rely on that, and what’s the process of submitting that sort of work?

Actually, I do much less than I used to. I do a small piece for The New York Times Book Review and I also do a piece for Wired. Those are my regular pieces, and I do almost exclusively editorial. Then once in a while, I will do a cover for The New Yorker. I send in sketches, and then there’s a lot of discussion and back-and-forth. You have to get the illustration past Francoise Mouly, and then you have to get it past David Remnick. The cover is an illustration with no text, so they put a lot of trust on the shoulders of the drawing – it makes sense that they put a lot of scrutiny into it. There’s a lot of pressure from me, from them, and also it’s an open competition. I have done enough covers now that I tend to get a response when I send one, which makes it a lot easier – I am very fortunate that I am not just throwing things into the ether with no idea if it does or doesn’t make it.

How do you start a new piece of work?

When I draw in a sketchbook, I use pencil. Pencil is definitely easiest, and I prefer to use a 2H – with some drawings, I use a whole range of pencils, but the 2H is the best. In art school, everyone would use soft pencils, but those get black too quickly. It looks kind of grey right away, and then you fill everything up and it gets so dark. You can’t add anything. But with 2H, you can keep drawing and still see the line. I have so many, but I tend to lose them or my kids steal them.

Do you ever go straight in with paint or ink?

Sometimes, yes. I use inks for the Sunday Sketches that I‘ve been doing. The unusual thing about that series is it was really unplanned. I wanted to do something on Instagram and I’m sketching all the time anyway, so I thought, I may as well post these things. I started about a year and a half ago and I found it was actually a lot of fun. I take whatever – an object or piece of paper – and I look at it until I see something. And what I see is totally un-plannable. It’s completely unpredictable and that’s why I don’t want to offer it to anyone as work – it’s something that just happens and that’s the charm of it.

Do you ever make decisions, sleep on them and then go back and change your mind?

All the time. Sometimes you look at something, and you think, that is awesome, and then the next day you look at it and you are horrified. Sometimes I do something three times over and think, this is terrible, and then I go back and find there’s some strength in there. You need the second day to realise the strength in something. On the one hand, I wish I didn’t waste so much time, but on the other, I really try and savour the inefficiency. I can be efficient with my work day and technology and everything, but one thing you must not – and cannot – be efficient with is creating. Once you start thinking about what works faster or better, you start ruling out mistakes, and that’s really awful. So I really try to be as inefficient as possible.

Thank you, Christoph, for sharing your studio and work for The New Yorker, Zeit Magazin, American Illustration and The New York Times, And so many other fantastic publications with us.