Future Anecdotes Istanbul

Berg auf, Berg ab durch die Straßen, in denen durchgestylte und einfache Cafes, Touristen- und Designläden mit traditionellen Werkstätten nebeneinander stehen. Unsere Redaktionsreise für die kommende Printausgabe, Slanted #24 – Istanbul, führte uns ins Studio Future Anecdotes Istanbul, wo die Grafikdesignerin Asli Altay uns erwartet. Um euch die Wartezeit bis zur Veröffentlichung Ende Oktober zu verkürzen, gibt es heute schon mal einen kleinen Vorgeschmack ...

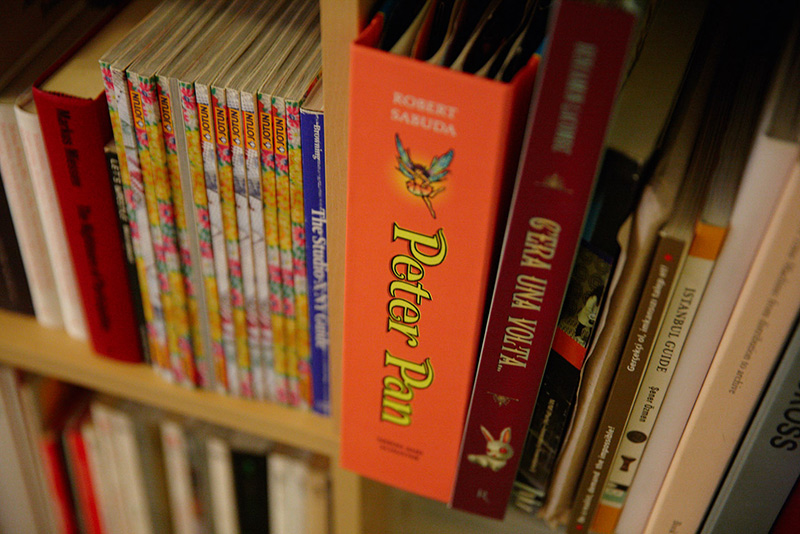

Future Anecdotes Istanbul (FAI) ist ein Designbüro, das ausschließlich mit Künstlern, Architekten, Kuratoren, Verlagen und Kulturinstituten zusammenarbeitet. Gegründet als Partnerschaft unter dem Namen Future Anecdotes in London, 2009, agiert das Studio seit 2011 in Istanbul als Erweiterung. FAI legt den Schwerpunkt auf Künstlerpublikationen, Corporate und Ausstellungsdesign.

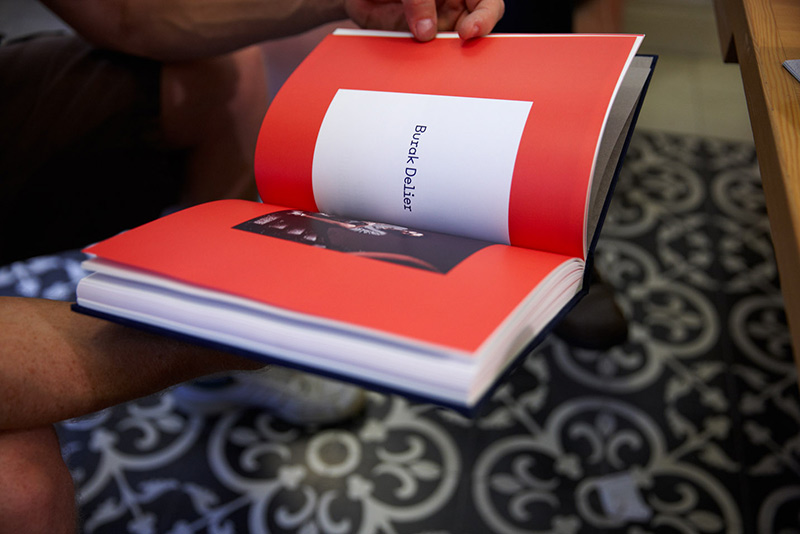

Den Namen des Büros hat Asli Altays gleichnamige Buch, das unter anderem in der Bibliothek des Tate Modern steht, bestimmt. Aslis Liebe zur Gestaltung liegt in der Kraft, Geschichten und Diskussionen durch das Visuelle, der Literatur und dem Raumerleben zu schaffen. Ihre Arbeiten erfassen Themen der Publikation und Publik-Aktion, Fragen der Darstellung und der Rolle des Design als redaktionellen Beitrag und ganzheitlichen Zusammenwirkens, statt alleinige Bereitstellung der Dienste.

Wir haben Asli einige Fragen zur Situation im Design in Istanbul und der Türkei gestellt. Seid gespannt auf ausführliche Interviews und viele Studioeinblicke der Istanbuler Designszene im Slanted Magazin #24 – Istanbul.

How would you rate level of education in Istanbul/Turkey? What is missing?

I am not in a position to rate the design education in Turkey, and rating is not a good method for positive impact, to start with. Having said that I studied my BA on Graphic Design at Bilkent University, in Ankara. It was a grounded, competitive department back then, quite strict on what is right and what is wrong on design. Still, it had a whimsical element that nourished bands and musicians to become, with great vocab, good sense of visuals and strong attitude. (It is always a good sign when students drop-off and start a band, for design schools anyway). The missing part might be content generation. I recall a lot of “lorem ipsum” going on during my BA studies, which is strictly sabotage for a designer to be. It tends to mold the profession towards service, removing the ability to challenge the given content, more importantly content-generation. This lack of self-reflexivity, and flat form-making attitude blocks graphic design to form a self-contained discourse. That’s what’s missing.

What do young designers or start-ups have to do to succeed in Turkey?

This obsession of being “successful” and “making it” seems like the biggest obstacle of being actually successful, I believe. It is an illusion, and it prevents you from failing, and you can not be very good at something by playing it safe and without experiencing failures. I’d suggest to try different methods and train until you find your own path. Study hard, become able to discover what you truly want to do and finally: specialise. When you do find it, you’ll want to be very good at it, and when you are good at it, there is a big chance you will be successful, at least succeed in terms of being happy, which might be harder than career success.

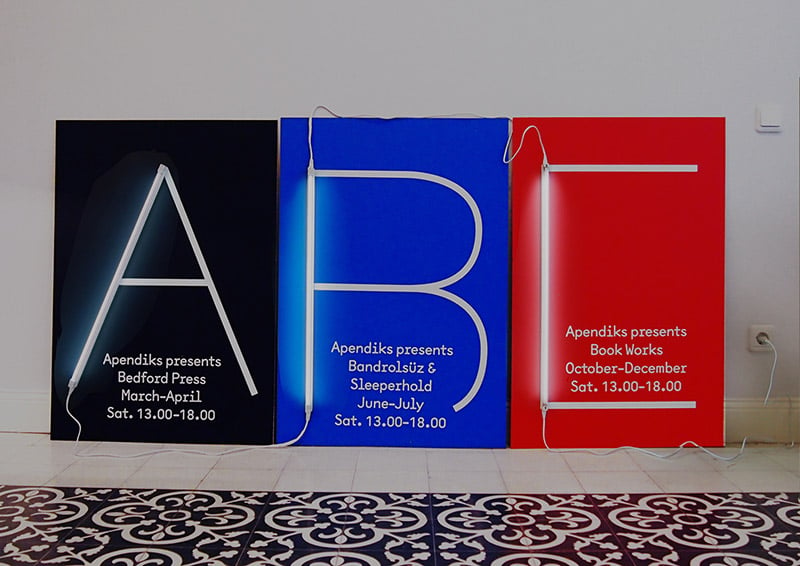

Apendiks, a project dedicated to host a specific publisher for two months, looking into their publishing practises. Publishers include, Book Works, Bedford Press, Sleeperhold, Bandrolsuz

Architects, interior designers and product designers of Turkey are more prominent than graphic designers, why?

I am completely speaking hypothetically here but I have observed that graphic design graduates tend to move towards advertising rather than pursuing a design oriented career within these borders. Some continue to think and work as a designer with a different hat on, but ultimately serve to advertising. This decision might be based on the financial facts of design vs advertising fees or the more galvanised image of advertisers. In comparison to interior designers and product designers I wouldn’t say that graphic design is less prominent, but design journalism, or design discussions are quite limited here and the exposure tends to be towards more “lifestyle” issues rather than the discourses themselves.

There are not many well known type designers in Turkey. Might the change from Arabic to Latin alphabet in the 1920s be a reason for that?

That is true, we have a fairly new alphabet, younger than my grandfather actually! And graphic design education itself is also fairly new. There is good room for growth.

Alexander Wagner, exhibition catalogue, 2013

How would you rate the knowledge of typography in Turkey?

If you ask a passer-by to compare Univers to Helvetica I wouldn’t think you’ll end up praising Frutiger over coffee. On the other hand, “knowledge” being larger than only the theoretical understanding of a subject and not limited to the lingo; I would say there has been a strong typographic sensibility amongst craftsmen for a very long time. For example, the local hand-made signage culture and lettering on many old apartment buildings prove that. In contrast with the LED signage, the bright but gaudy and tasteless information that surrounds us today, these hand-made and well thought-through typographical statements re-assure me.

Dismantling An Archive, exhibition at SALT Galata, 2014

What is your hope for the future?

World peace.

An Archipelago from the Mediterranean, Project for 5th Marrakech Biennial, Can & Asli Altay, 2014

Fotos: Christian Ernst, FAI

Slanted Magazin #24 – Istanbul

Herausgeber, Design und Redaktion: Slanted Publishers

Veröffentlichung: Ende Oktober 2014

Format: 16 × 24 cm

Umfang: 288 Seiten

Sprache: Englisch

Subskriptionspreis: 15 Euro, danach regulär 18 Euro

Auslieferung zur Veröffentlichung